Lecture Reports

The First “Great East Japan Earthquake Tour” (3.11) Fukushima, Japan

Testimonial from Ms. Keiko Enei

- Lecture Date

- March 23, 2013 (Saturday)

- Venue

- Royal Hotel Maruya (Haramachi, Minamisoma City, Fukushima Prefecture)

- Speaker

- Ms. Keiko Enei, a patient affected by the disaster in Odaka Ward, Minamisoma City

Thank you so much for taking the tour today. But since we had a bus, unfortunately we couldn’t go deeper into the city and witness more remnants of the disaster and visit my house.

I actually have big pets, two horses. I wanted to show you them along with my cows and devastated fields caused by the tsunami. My house is in a terrible state with rat droppings in the barn, storehouse, and outhouse. The house that was newly built two years ago barely survived, but I wish you could have seen it.

I am a board member of the Rheumatism Patients Association, and actually, when the JPA first asked me about this tour through my branch manager, I refused.

As for the reason, I said, “why are they coming here now like on a wild-goose chase”?

At that time, the branch manager said, “Okay,” but after a certain amount of time had passed, she asked me again, “Can you please help them? “

So, I accepted because I felt that it had been two years and that they were not just “wild-eyed”.

I would like to talk a little about the relationship between the earthquake, tsunami, and the nuclear accident.

First, there was an earthquake, then the power went out. Due to the tsunami, the power lines were cut and we could not watch TV. That day, I ate dinner in the dark and went to bed in my clothes. The next day, the weather was fine, so I was cleaning up. I would never have dreamed that a tsunami hit. We were only about three kilometers away in a straight line. The sound of helicopters and sirens from ambulances was so loud. It was broadcasted that those who had blankets, etc. were encouraged to bring them to the evacuation area.

Then, at about 3:35 that day, I suddenly heard an explosion. My house is 17 kilometers away from the nuclear power plant, and I was thinking, “What is it, another earthquake”?

We were cleaning up our house without being told anything, or rather, without knowing anything. Then, we were told to evacuate the next day or so. But I didn’t evacuate for three or four days. I had rheumatism and my legs hurt, and I could not use the toilet in the gymnasium unless it was a Western-style toilet.

Eventually, a helicopter flew overhead. When it spotted someone, it announced an order. “You have to evacuate”. I didn’t experience the war, but I guess it was like gunfire. So, I spent four days hiding in the shadows, turning off the lights at night, eating, and not going outside during the day.

We evacuated to the horse park in the mountains because the buildings next to the nuclear power plant were going to be destroyed. However, we were told that it would soon be dangerous there as well, so we had to go to Nakadori or Aizu, so we fled.

At first, I spent a month at an old hot spring in Inawashiro, which they were planning to close in the next three months. At that time, there was no exemption for the accommodation fee, so it cost 3,000 yen per day. We were told to make our own meals, so we did that, and we cleaned the big bathroom by ourselves. We didn’t know what was going on anymore. We looked for temporary housing or rented housing, but we couldn’t find anything. After that, we went from place to place to visit relatives, and finally found a place in Kitakata City, near Nishi-Aizu, where there was heavy snowfall in the mountains. I evacuated there with my family.

My husband stayed in Minamisoma because of his job, and my parents and I spent six months there with our son. However, we could not drive around the heavy snowfall in the area, so we looked for a temporary shelter or rented housing that had a view of the sea. It was not easy to find one, but we finally did in December of the year before last, and it is the temporary housing that we are showing you today.

My father and mother have lived in Minamisoma City for 80 years. They were living in a different place and putting up with it without saying anything, but one day my father said to me, “The sun rises in the mountains and sets in the mountains in Aizu,” until then, he always saw the sun rising over the sea and setting over the mountains. It was very hard for the my elderly parents to live in a different place.

After we came to the temporary housing in Minamisoma, I could see by their faces that my parents were very content. I realized how good it is to live in the place where you were born. I was not able to do anything filial for my parents, but I felt proud that I was able to do something for them. Now I live in a temporary housing facility that is warm and I can drive home in about 15 minutes.

After we came to the temporary housing in Minamisoma, I could see by their faces that my parents were very content. I realized how good it is to live in the place where you were born. I was not able to do anything filial for my parents, but I felt proud that I was able to do something for them. Now I live in a temporary housing facility that is warm and I can drive home in about 15 minutes.

Even though we are having such a hard time, we don’t want to feel that we were victims of the nuclear accident caused by the earthquake. I want to believe that this situation will remind the world how dangerous it can be living with nuclear power, it can be very scary. This thought makes the situation somewhat bearable.

Unlike me, many families were torn apart.

So, it’s really stressful.

When I meet people I know in town, I can’t even recognize them because their faces have changed. It was a stark reminder that this is what happens when people have psychological problems caused by trauma. The psychiatry department, which used to have very few patients, now has many more because of sleep deprivation or other ailments.

What I have learned from this disaster is an appreciation for the basic things in life. So, a small temporary house is enough. I don’t need such a big house, and I don’t need more than three changes of clothes. I don’t mean to brag, but I only wear clothes that cost about 3,000 yen in total from Uniqlo, and that’s enough for me. I think I lived too extravagantly in the past, and I wonder if that is why God got angry with me and impressed upon me to be a little humbler as people were in the past.

Listening to everyone’s self-introductions today, I realized that it was a good idea to have everyone reasses the current situation.

The reports only tell part of the story and focus on the positive developments in the recovery process, but it is not reality. I’m glad that everyone was able to see the situation firsthand.

Finally, let me tell you a little about my illness. I have rheumatoid arthritis but have been in remission for about 20 years without taking any medication. I used to boast that I was medication free.

But in October of 2010 (seven month after the disaster), my head started hurting so badly and I realized it was not a normal headache, so I went to the hospital and found out that I had high blood pressure. I was told that my blood pressure was over 200 and could not be measured, so I started taking medicine. Then, when I moved into this temporary housing, I felt somewhat relieved but suddenly my rheumatism came back so I started taking medicine again.

Now that the medication has taken effect and I am feeling calmer, I am hoping that it will go away. So I realized that stress can manifest itself in people with debilitating results.

Thank you very much.

Ms. Enei was very kind by allowing us to visit the temporary housing where she lives and guiding us around Odaka and Namie Town.

Editorial Department

The Fourth “Great East Japan Earthquake Tour” (3.11) Fukushima, Japan

Mini Symposium

- Lecture Date

- Saturday, March 12, 2016

- Venue

- Royal Hotel Maruya (Haramachi, Minamisoma City, Fukushima Prefecture)

Moderator: Mr. Tateo Ito

“Reconstruction Support Activities for Community Creation in Minamisoma City”

Department of Disaster Medical Support, Fukushima Medical University

Department of Neurology, Minamisoma City General Hospital Mr. Masaaki Odaka

Nice to meet you all. I am Masaaki Kotaka, a doctor here helping with the reconstruction activities. I was impressed with your stories. Even though I’m sure you are occupied with your own health circumstances, from the beginning you must have felt or thought something when you came to Fukushima to see the disaster area.

Nice to meet you all. I am Masaaki Kotaka, a doctor here helping with the reconstruction activities. I was impressed with your stories. Even though I’m sure you are occupied with your own health circumstances, from the beginning you must have felt or thought something when you came to Fukushima to see the disaster area.

I quit my job at the university hospital in Tochigi prefecture four years ago, and moved here in April 2012. If I were to tell you why I quit my job at the university hospital, it would take more than 30 minutes, so I will leave it at that and talk about what I felt as a doctor and what I have actually been doing since I came to this town. Hopefully, you will feel inspired by my story.

What I had to do in the disaster area has nothing to do with medicine. I consider myself an unusual doctor and I hope you can appreciate my involvement here. I’ll talk about my medical practice at the end.

I was born in Saitama and I am a neurologist. My areas of expertise include multiple sclerosis and adult Still’s disease.

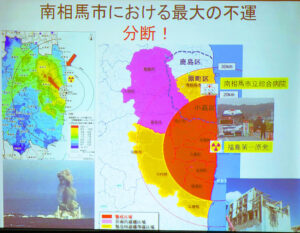

Looking at your itinerary for today, you are visiting Odaka Ward and Yoshizawa Farm in Namie Town. Minamisoma City is the first area in the world to be hit by a triple disaster: earthquake, tsunami, and a nuclear power plant disaster.

The area where we are now is about 25km from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Odaka ward is within 20km and was a forbidden area. The distance from Tokyo to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant is more than 200km. It would not be fruitful to talk about what happened at the time of the earthquake, so I would like to talk about what has happened since then. As you can imagine, the city of Minamisoma experienced an outflow of population after the earthquake. Comparing the population distribution at the time of the earthquake with 2014, the percentage of elderly households has increased as more and more younger generation residents have left the city. In 2010, Minamisoma City had an aging population rate of 25%, but after the earthquake, the rate quickly rose to 33%, and the city has become a “super-aging society” where one out of three people is over 65 years old. In this sense, the area has quickly become a forerunner of what Japan will be like 20 years from now. It is estimated that the population distribution in Tokyo will be similar like at that time. If you refer to a map, you can see that the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant straddles the towns of Okuma and Futaba. Minamisoma City is located on the north side of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, which was originally a merger of three towns in 1995.

The area where we are now is about 25km from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Odaka ward is within 20km and was a forbidden area. The distance from Tokyo to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant is more than 200km. It would not be fruitful to talk about what happened at the time of the earthquake, so I would like to talk about what has happened since then. As you can imagine, the city of Minamisoma experienced an outflow of population after the earthquake. Comparing the population distribution at the time of the earthquake with 2014, the percentage of elderly households has increased as more and more younger generation residents have left the city. In 2010, Minamisoma City had an aging population rate of 25%, but after the earthquake, the rate quickly rose to 33%, and the city has become a “super-aging society” where one out of three people is over 65 years old. In this sense, the area has quickly become a forerunner of what Japan will be like 20 years from now. It is estimated that the population distribution in Tokyo will be similar like at that time. If you refer to a map, you can see that the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant straddles the towns of Okuma and Futaba. Minamisoma City is located on the north side of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, which was originally a merger of three towns in 1995.

Originally, the three towns of Kashima, Haramachi and Odaka were merged to form one city. The merger of towns and villages is always a messy affair, but we finally restarted as one town and were living in harmony when the earthquake happened. As it turns out, Odaka Ward is within 20km of the nuclear power plant, Haramachi is between 20km and 30km, and Kashima Ward is outside of 30km. This, more than anything else, is considered to be the greatest misfortune of Minamisoma.

I won’t say much, but most of the residents of Odaka Ward evacuated to Kashima Ward because they could not live here. People from Kashima and Odaka Wards now live together. Most of the people in Odaka ward qualify for a guarantee and receive money, while the people in Kashima ward didn’t receive guarantee even if their houses washed away. Even so, it has been five years now, and things are gradually getting better. I came to this town one year after the earthquake, but it was still in the midst of confusion.

I won’t say much, but most of the residents of Odaka Ward evacuated to Kashima Ward because they could not live here. People from Kashima and Odaka Wards now live together. Most of the people in Odaka ward qualify for a guarantee and receive money, while the people in Kashima ward didn’t receive guarantee even if their houses washed away. Even so, it has been five years now, and things are gradually getting better. I came to this town one year after the earthquake, but it was still in the midst of confusion.

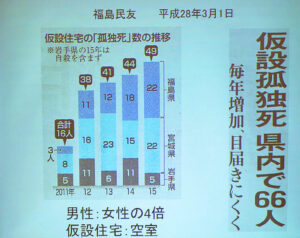

When I first arrived here and started providing medical support as a doctor, I noticed that the number of people who had been forced to take refuge in temporary housing because their homes were swept away became depressed or turned to alcohol, in short, the number of isolated people had increased. The other day (March 1), the Fukushima newspaper still carried an article titled “66 hard to reach people died alone in temporary housing in Fukushima, a number that increases every year”. Of the three prefectures affected by the disaster (Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima), Fukushima Prefecture has by far the highest number of “lonely deaths”, or “lonely suicides”. And the reality is that the number is still increasing. This is especially true for men. Some people have committed suicide by writing on the wall, “If only the nuclear power plant were not here,” or “I have lost the will to work”.

I anticipated that the situation might be the same here. My reasoning is that, after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in 1995, about 6,000 people (earthquake and related deaths) died over a four-year period, and the data shows that 244 died alone. It was known that middle-aged men, many of whom were unemployed and alcohol dependent or suffered from chronic diseases, were high risk for lonely deaths and suicides after the earthquake. So, of course, it was easy to imagine that these tragic deaths could also occur in the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake.

I wanted to reduce the number of such deaths as possible, so I went to the temporary housing facilities and held salon activities such as talking and playing games together. I didn’t consider this gesture to be anything special.

It’s obvious from the pictures that most of the people involved were women. I think women are stronger than men in such adversity. I thought this point had a relation to the number of men dying alone.

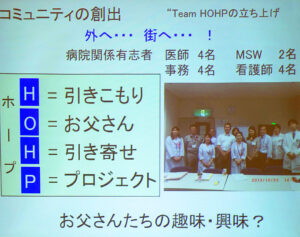

So, the hospital staff and I discussed, talking to the isolated men to see if they had hobbies, or if we could get them out and do something together. Then, we decided to do community creation activities, and started Team HOHP [H: Hikikomori (shut-in) O: Otosan (father) H: Hikiyose (attraction), P: Project]. We formed a team of volunteers and had many discussions about what we could do to interest the men.

What I did was to start a woodworking class in January 2013, which was about two years after the disaster. I didn’t have any skills to teach woodworking, so after consideration, I asked for help from a building union in Minamisoma City. I met with the representative of the union and asked him if there were any craftsmen who could teach woodworking classes to prevent isolation. He made an immediate decision that his members would teach the enter group. And so, we started every Sunday morning. We were blessed with this opportunity but had to decide how to secure a studio and tools, but with the help of various donations, we were able to get started.

We didn’t want to just hold a woodworking class, but we also wanted to create something special. First of all, we decided to make woodworking products that could be placed in public facilities or that would be useful for the reconstruction of the town. For example, instead of making plastic models for a hobby, we thought it would be a good idea for everyone to finish woodworking projects together. We also made things that would benefit kids as well as park benches, display shelves for the café at the ward office, bookshelves for the school library, planters for the town and signs for businesses.

The project was well-received locally, and the Fukushima Minpo published an article titled “Working together to create woodwork”. We also received a letter of appreciation from the city, so I feel that we have received recognition from the public.

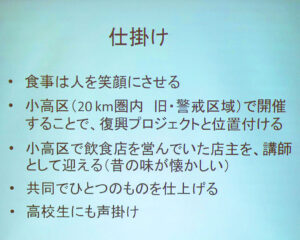

I was so pleased with the woodworking project that I had another idea. But let me take you back to about one year after the earthquake. When it was safe to enter the evacuation zone, I visited Odaka Ward. One day I saw a sign in front of the station, “Kashi (Sweets) Kobo Watanabe,” that read, “We will definitely revive Odaka”. The owner of the store probably wrote this before evacuating. When I saw it, a strong impact was burned into my mind. I wanted to do something for this “Kashi (Sweets) Kobo Watanabe”, so my idea was to hold cooking classes in Odaka Ward. I decided to hold the first cooking class on September 11, 2013, even though Odaka Ward did not have running water at that time.

Since there was no water available, they made dumplings which don’t require much water because the water tank was not readably available. So, they tried to use as little water as possible. The “Kashi (Sweets) Kobo Watanabe” has now moved to Haranomachi Ward and continues to operate. It’s doing quite well. Again, I do not have the skills to teach cooking. I thought about it again.

In a hospital, there are a lot of nutritionists and people who are good at cooking. When I asked one of them, if she could help me, she immediately said, “sure”. The people of Haranomachi are friendly, kind, and willing to help. I told the Odaka ward office about my plan and schedule. As I mentioned, there was no running water, so we had to fetch it remotely, and unfortunately, we couldn’t use the toilets. The ward office had running water, so we asked if we could use their toilets.

Then, five days before the event, the ward office called me and said they would provide water only for this occasion, so we were fortunate to have it available at the venue. I’m glad our request paid off. I think it is more effective to put silent pressure on the government i.e. don’t tap on the desk and say, “What are you going to do?” but instead request without raising our voice, and present a strong proposal as to why our request should be considered. The government acted accordingly.

In Odaka Ward, there are various restaurants that have been evacuated. We call the owners one by one and ask them if they would be willing to teach a cooking class in Odaka Ward, which we do about once every two months.

It is simply fun to cook and eat food. Not only in Minamisoma, but also in Iwate and Miyagi, there are many cooking classes being held within the temporary housing community, so it is nothing special. It’s a practical initiative in support of the reconstruction. However, we came up with the idea of having the owners of the restaurants in the former evacuation zone come to the events, so that everyone could enjoy the taste of the past.

There is a famous chef from Odaka Ward named Yoshiteru Nishi. He is the exclusive chef for the Japanese national soccer team. He also has a book titled “Samurai Blue Chef”. When I heard that such a famous person was in Odaka Ward, I invited him to come to the event. To my surprise, he accepted my invitation and about 60 people attended. We couldn’t even fit them all into the hall. I felt that the potential of Odaka Ward was so amazing.

In my opinion, many Japanese men are shy yet proud individuals. When holding an event, it is best to have one woman for every five men. If we try to do something with five women and five men, the women are usually more outspoken, so the men feel intimidated. Therefore, when we hold such events, it would be more effective if the ratio is one woman for every five men.

When we tried to involve the men, they were quite shy, so we gave them specific roles &/or activities. Also, it is important to motivate them by saying, “I’m counting on you, Mr. XX. For example, in the woodworking class, if you say, “Mr. ○○, please cut this piece of wood for me,” they may say, “Yes, of course”.

It is also important that the products they make are placed in public facilities and are useful to people. “I made that,” they say, and their woodworking skills continue to improve. I learned that by doing so, men will also become more active.

So far, I have talked about community creation activities. Finally, I will talk about my medical practice. I am a neurologist, and I am faced with the question of what to do with patients with intractable diseases in my role here.

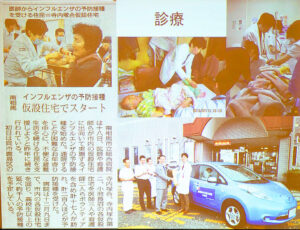

There are five ALS patients in this town. I see about three of them. One of them is on a ventilator. I was wondering about the best way to help them, so I decided to do home treatment which I never did at the university hospital. Most general hospitals in Minamisoma City had home care departments after the earthquake. So, I had friends who were doing home care. That’s why I was able to get into it, and together with the doctor from the home care department, I am now doing home care for neurology.

The only problem was that we didn’t have a car. All the doctors used their own cars to make house calls. Because they worried about insurance in case of an accident, they decided to purchase an official car.

I wrote a letter to Nissan Motor and asked if they could provide a car for us. They said they would not donate a car, but would lend us one instead. There was a ceremony to present the car to us, and a company official came to give us a big key and they even made a special sticker. We are still using it as a house call vehicle. At first, it was a one-year lease. We were grateful for that, but after a year, we were told that it was too much trouble for them, so they finally donated the car to us.

Since the temporary housing complexes are densely populated, we thought it was inevitable that illnesses such as the flu would become widespread. So, we volunteered to give flu shots to the residents. Including now we’ve done this every year.

Finally, we are talking about intractable diseases, and I am wondering how to take care of these patients. For starters, we need to research the lifestyles of intractable disease patients. There are two patient associations, the National Parkinson’s Disease Friendship Association and the Dementia Patients and Families Association. Unfortunately, these are the only two that exist. I am also a member of the associations, and together we participate in beneficial projects.

As is the case everywhere in Japan, there is a shortage of caregivers. This is an untenable situation for the affected areas. Because mothers of child-rearing age have evacuated, caregivers, care managers, and nurses have all left, and there is nothing we can do about it. We decided that the only way to solve this problem was to create and train caregivers here, so I became a lecturer at such a course. We also need to revive the number of seniors involved in human resources. There are a lot of retired people who are still very active, so I would like to encourage them to work for the town before retiring.

My other activities include the following: I am a host at a mini-broadcast station called Community FM, where I talk about the reality of healthcare and other topics. Minamisoma City is not very safe these days. Thankfully, a lot of people have come to help with the recovery, and some of them are a bit rude, so there have been some skirmishes at local bars.

So, we decided to form a team to patrol the area by car. I also like to write, so I published essays and so on.

So, we decided to form a team to patrol the area by car. I also like to write, so I published essays and so on.

Speaking of Minamisoma City, have you ever heard of “Soma no Umaoi”? If you’ve never heard of it before, please remember it today. This is a big event held in July. Samurai on horseback parade through the town, horse races are held, and people dress up as samurai and participate in various events.

I have no experience riding a horse at all, but when I saw the horse race for the first time, I thought it was really cool and that I should definitely participate. In the meantime, I was introduced to a place where I could learn to ride a horse, and I practiced and practiced even in the rain and cold winter snow. And in 2014 and 2015, I rode a horse through the city wearing armor and dressed as a warrior.

The first legend is that during the era of Taira no Masakado: more than 1,000 years ago, Masakado released wild horses and conducted military training with them as the enemy. However, this is a big lie, and in reality, the history is only about 400 years old, but it was supposed to be remembered as a more romantic event.

I am not only providing various kinds of support here, but I am also doing something that I enjoy. You could say it was an unintended benefit for me during these challenging times. I am preparing to participate in the horse chase again this year, so I am very much enjoying my time in Minamisoma.

Even though people are still suffering in the disaster area and we adamantly petition Tokyo for support, their response has become tepid. The urgency has faded away too much. I hope one day soon to announce to the people of this area that this tumultuous period will be over, and the town will become a fulfilling and enjoyable place to live.

Thank you very much for your attention.

-

- (Q) Are the woodworking and cooking classes only for men?

- (A) No, in fact there are many female participants. However, I thought that if I didn’t put “men’s” in my appeal, men would not come. If we start out by saying that anyone, male or female, is welcome, especially in cooking classes, the number of participants will be overwhelmingly female. That’s why I decided to call it a “men’s cooking class” so that women would be welcome.

-

- (Q) Why did you decide to come to this place?

- (A) I decided to come to this place because as an associate professor at the university I was wondering what the future held for me. I was not interested in becoming a professor. It became more and more of an administrative position, and I became involved in the management of the hospital, away from the patients. It was a valuable experience, but I began to feel disconnected from the field. Just when I contemplated quitting the university, the earthquake happened. I’m from Saitama, but I thought I would go to Fukushima before returning to Saitama, and once I went to visit, I found that there were not enough doctors, so I thought I would stay for one or two years, but I found myself here for four years, and I still have no intention of going back.

After the tsunami

Disaster Victim, Ishinomaki City, Miyagi Prefecture Ms. Akemi Suzuki (Multiple Sclerosis)

As I listened to Dr. Kotaka’s speech, I thought about what I should say for 15 minutes. There is no end to what I have experienced in the past four years, but today I would like to talk about my time in the temporary housing and current situation in the reconstructed housing. First of all, we were the last ones to relocate to the temporary housing in October 2011.

As I listened to Dr. Kotaka’s speech, I thought about what I should say for 15 minutes. There is no end to what I have experienced in the past four years, but today I would like to talk about my time in the temporary housing and current situation in the reconstructed housing. First of all, we were the last ones to relocate to the temporary housing in October 2011.

When there were no rooms available and we thought we would not be able to get in because we did not qualify for either the handicapped or elderly categories, there was a cancellation and we were asked to move in to the temporary housing in Ishinomaki.

We moved in there because it was in a good location: the hospital was close, the bank was close, and shopping was convenient. I don’t know about other places because different companies built different temporary housing, but ours was a house with a lot of steps.

I had to crawl and walk to get over the steps, which was really hard. One day, one of the support groups told us that there was a notice from the government that if there were any problems in the temporary housing, they could be fixed at public expense.

Someone gave me a copy of the notice and told me, “Ms. Suzuki, since you don’t know how many years you will live here, you should use this provision in case something happens and have it fixed so that you can live comfortably.

However, when I asked the city office to retrofit my room, they didn’t take me seriously at all, and finally asked me if I had a disability certificate. When I told them that I did, the person at the counter asked me to make a photocopy of it, and when I asked if there was anything else I needed to do, they said that people with disabilities should go to the disability welfare section to go through the procedures. I was told that I must pay the total amount for the retrofit, they said, “In Ishinomaki, everyone has to pay the actual cost. “

I then brought out the form that I had received from the support group and said, “Actually, I have this form from the government, don’t you know about it”? The staff were surprised. In Ishinomaki, there was a lot of confusion, but there were many cases where notices from the top did not reach the front line.

So, I negotiated and finally got the OK in December, and the work started in January 2012. There were steps everywhere, so they eliminated them and added handrails and a bath. In the bathroom, there were separate taps for hot and cold water, but since I have a slight sensory impairment, I tried to get them to change the taps to mixed valves in case I burned myself. Initially, they said no but in fact it was approved.

When the work was completed, it was determined that this was the first time Ishinomaki City had such work done through a local government provision. It was so unusual and valuable that the city hall and local care managers came to take pictures. I wondered what was going on, but that’s how confused Ishinomaki was, and after a lot of wrangling, we ended up with comfortable temporary housing. When I moved to the housing, I didn’t know anyone. When I’m feeling well, I can talk and walk around like I do now, but when I’m not feeling well, there are days when I can hardly wake up, my memory is not clear, and I can’t speak properly. I wanted someone to support me, but I didn’t know anyone around me, and I felt like I couldn’t go out on my own.

Anyway, my feeling was that I couldn’t live in the temporary housing unless people understood me. For about two years after that, if I told people about my illness when I was feeling good, they would say, “You were so healthy the other day”, so if I went to an event when I was feeling good in the morning but bad in the afternoon, I would be fine when I went, but by the time I left, I couldn’t walk anymore. Gradually, people came to understand my condition.

At first, people thought I was somewhat strange, and then a few people started to understand my illness. They even started to notice my physiological change before I did, saying, “Akemi, you don’t look so well, maybe you won’t be able to walk soon”. That made my life a lot easier.

There were many problems with the temporary housing, and I recommended some necessary upgrades such as double sashes, insulation, and ventilation fans for the ceiling because mold was growing, but everyone helped me and it was very fulfilling.

I spent four and a half years there, and when I was finally comfortable, I won a lottery allowing me to move into a newly reconstructed housing unit. It was also an apartment complex that would be the centerpiece of Ishinomaki’s reconstruction project. Many other people with disabilities as well as able bodied people wanted to move into this building, but it filled up quickly. Fortunately due to a cancellation, I won the lottery choice and opportunity to live there. My apartment was on the second floor, but that was okay because there was an elevator. The problem however is that I have a balcony in front of my unit, and there is a walkway in front of it. Many people use the walkway and that bothers me a lot because it affects my privacy. Normally, if I were on the second floor, I wouldn’t mind wandering around in my pajamas when I’m not feeling well.

For security purposes, usually the entrance to this type of building are on the other side of the balconies. However, this buildings’ entrance is on the same side as the balconies. When I mentioned it to the builders they told me that it was originally intended to be a housing complex for the younger generation from Kanagawa Prefecture, but it was rejected, and Ishinomaki chose it because they wanted to build it quickly and changes in the design would take more time.

My unit is barrier free, however, the woman living next door has a living and dining room downstairs and bedroom upstairs. There are a lot of units like that in this building, which would be difficult for me to live in. Again, the builder told me that this was a popular single-family home concept in Kanagawa Prefecture.

However, the elderly people who won the lottery and were offered a maisonette (a unit that is divided into two or more floors) would have to decline the offer as it was not barrier free. These cancellations are then passed on to people like us who have nowhere else to go. If it had been a two-story house, I would have cancelled my application as well. Sometimes the government tries to offer such opportunities without thinking it through. I don’t want to think that Ishinomaki is particularly like that.

Then there is the same reconstruction housing, but with a 20-year lease. The government failed to build it after the Kobe earthquake and has been making a fuss about it for a couple of years now. The elderly people in their 80s who live alone have nowhere to go. They built such a house in Ishinomaki. Now, people in their 60s and 70s are living there. In 20 years, they will be in their 90s, right? I have tried to contact the city many times to find out what they will do, but they only listen to the voice of a citizen. On the contrary, they said, “Even though you have a disease, you can walk and talk on your own, and you can come to us like this. Don’t worry about other people, just think about yourself. Right now, you are the most important thing. I don’t like the idea that I’m good and that’s it. There are elderly people who are left behind and handicapped people in wheelchairs, so I want to think about these people as well. I wonder why people don’t think about how to avoid failures in reconstruction housing, since they failed so badly in temporary housing.

However, those of us who are in the area can understand such things, but those around us probably only see the news of people being moved from a nice temporary housing to a nice reconstruction housing. The situation in Ishinomaki is like this, and it is not quite the same.

I want people to understand that even if they win a reconstruction house, they have to cancel it because they can’t live in it. We are trying to make life a little easier for the elderly, but it seems that the government officials in Ishinomaki can’t reach us, which makes me sad every day.

Situation of Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant Damage

Mr. Masao Sato, a survivor from Namie Town

I really felt that in my experience the government wasn’t very helpful at all during the Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. If I say anything further, it will just be perceived as another sneer about the administration. So, I’ll just leave it at that.

I really felt that in my experience the government wasn’t very helpful at all during the Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. If I say anything further, it will just be perceived as another sneer about the administration. So, I’ll just leave it at that.

In hindsight, there’s nothing more I can say. People who had real-time information about the earthquake and tsunami, such as the government, quickly fled to safer places. Those who did not receive such up-to-date information fled to places that had high levels of radiation. This was a typical scenario in Namie town.

This is going to be a bit of a rambling story, but I would like to talk about the time from when the earthquake struck until when the situation settled down.

My house is now in a restricted residential area. This area was delineated after the disaster. When the earthquake struck, I was in Mizukami, Gunma Prefecture. I recall drinking tea while I anticipated the birth of my daughter’s second child. When the TV broadcast the earthquake, I called my son and he told me that the beaches of Fukushima Prefecture had been completely wiped out. Off course I was planning to stay in Gunma but decided to return home.

As we left Gunma Prefecture, we realized that the Kanetsu Expressway was closed. After going down Route 17, we passed by way of Gunma Prefecture’s Karakkaze Highway, then took the Watarase Highway, passed Nikko, and came out on Route 4. It was scary because there was a power failure and no lights were visible. I had to slow down and try not to hit anything. When I came to Sukagawa and Shirakawa, the dam was broken. The ground was so bad that Route 4 closed. This time we went east and came out in Miharu. We left in the early evening, but it was dawn when we reached Futaba Town.

I heard the people of Futaba town saying, “it’s hopeless,” as they fled down Route 288 toward Koriyama. By the time I entered Futaba town, large rescue buses were coming into Okuma and Futaba towns from behind. I think the towns that have a disaster agreement with each other received emergency information. However, Namie town did not receive any information. Later, officials said that they sent the emergency information by fax, but there is no way to confirm that now.

When we arrived in Namie town, people were cleaning up their houses, including dressers that had fallen down in the earthquake. We heard that the nuclear power plant was dangerous, so we stayed for about three days in the Tsushima area where we had relatives. Looking back on it now, it was the place with the highest radiation dose. Then the nuclear power plant exploded, and we decided to flee to Nakadori for the time being, and after others had fled, the people of Namie town also fled.

At a sports center in Koriyama, we conducted a screening to measure body radiation doses. Those who were exposed to radiation took showers. In Koriyama, there was no place that would accept us. We were told to evacuate to the prefectural agricultural center, where we stayed for about two weeks. After that time, I was asked to support the building of temporary housing in Hamadori, so I could only be with my family in Koriyama on weekends. Then I went to Shinchi and Soma to also build temporary housing. Later, I went to work at a hotel in Haranomachi, and as I drove by Route 6 one morning, I saw the first Self-Defense Force motorcycle squad, followed by a six-wheeled armored car, just like you would imagine in a war. They were just unloading their machine guns. Next came the big trucks and trailers, and then the jeeps with the Red Cross on the back. I worked while watching them.

Then, people in Namie Town were told to evacuate to Tsuchiyu or Inawashiro. We stayed at a hotel in Inawashiro and my dad was admitted to a hospital there because he was sick with cancer. Next, we decided to enter the temporary housing in Onodai, Soma City. However, because of my work, I could not stay in the temporary housing, so I found a rented house through a friend and moved in there and again was separated from my family. At that time, my relationship with my wife started to deteriorate. She had difficulty sleeping and would threaten me with knives on occasion. It was a terrible situation.

I was going crazy. I couldn’t sleep or eat without taking medicine. But I felt I had to work, so I was working on the construction of temporary housing because it was ordered by the Prime Minister. After the temporary housing in Shinchi-machi was finished, I went to Shirakawa City and then Funehiki Town. At one time, I couldn’t sleep or eat for about two weeks. My eyes deformed and I lost about six kilograms.

I decided that it was better than doing nothing, so I went around to work on the reconstruction of hospitals, hotels, and facilities for the elderly. At a hotel called Hiten in Soma City, I was surprised to see the boots of the Self-Defense Forces as they collected the corpses lined up at the entrance.

After that, I was separated from my family for a long time, sometimes not contacting them for a month. I was worried about the dog I had left at home, and when I talked about the dog, my wife asked me which was more important, my family or the dog, and we started fighting. She also complained about me coming home drunk. I thought about getting a divorce.

My old friends had gone to Nakadori, and I was alone in Hamadori, living a life where work was my hobby and purpose. From my own experience in the first year or two after the earthquake, I felt that the situation would only get worse. I wondered why the lessons of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake had not been applied.

Then, after another year had passed, I was able to meet Dr. Kotaka. I have always liked hiking and fishing, so I went hiking in the mountains with him and the people he knew.

Perhaps it is because the temporary town hall of Namie Town is located in Nihonmatsu City, but it seems to me that people are just talking about idealism from afar without looking at reality. When someone started growing vegetables in Namie Town, the town, prefecture and the agricultural cooperative were against it due to possible radioactive contamination. But when that person started appearing on TV, the same officials didn’t voice their previous concern regarding the risks. It seemed to me that because the person was becoming somewhat famous, the town, prefecture, and agricultural cooperative representatives decided to support them.

After that, my physiological condition improved somewhat, but I had become addicted to prescription drugs. I feel relieved to sleep when I take them, and I feel like I wake up in the middle of the night if I don’t. Now I take three kinds of sleeping pills. When I meet people, I ask them what they are taking, and they brag about the pills they are taking. This was unthinkable before the earthquake.

These days when I go to work, my dog looks sad, it’s as if he remembers that we left him behind right after the earthquake. He is really happy when I come home from work. Even though my old house is gone, I’m starting to feel calmer and more relaxed. My wife used to have a lot of fun with many people in the temporary housing, but after she left there, she had nothing to do. She now thinks of various reasons to go there everyday.

As Dr. Kotaka said earlier, I think it is important to find ways to connect with society and find enjoyment in the future.

Even if we make friends with people in the temporary housing, we will be scattered again because we will be moved to a new place by lottery. And when or if we build a new house, we have to start all over again to make relationships, so we often go back to see our acquaintances in the temporary housing. I am looking forward to seeing how the government and the administration will think about these issues. As we can’t go back to Namie Town anymore.

At my age, I maybe only have 10 or 15 years left to live. I would like to die happily in that time. My son is still single and has been transferred to another place, but there is one thing I have told him. I asked him to protect my grave and Buddhist altar no matter where he goes. There is plenty of work to do, and I enjoy it when I am working. When I get home, I play with my dog, lie down, and watch TV, and I think that is the best way to relax. Maybe it is my luxury time. I just feel like my hometown has been ignored and I miss it.

The Fourth “Great East Japan Earthquake Tour” (3.11) Fukushima, Japan

Listening to the stories of disaster victims

- Lecture Date:

- Sunday, March 13, 2016

- Venue:

- Capital Hotel 1000 (Rikuzentakata, Iwate)

- Speaker:

- Mr. Akira Sato, a survivor from Rikuzentakata City (Lives in Morioka City)

Mr. Kenichi Chiba, the president of Iwate Nanbyoren (Intractable Disease Association)

I am Akira Sato. I have been working with Mr. Kenichi Chiba, the president of Iwate Nanbyoren (Intractable Disease Association), in one of the volunteer groups, I would like to share some of my experiences with you.

My home town is Rikuzentakata City, and I lived about a 10-minute walk from here. There used to be a public disaster housing complex nearby that looked like a large apartment building, and I lived on the other side of it. My place was about 250 meters away from the beach. Those of us who lived in coastal areas have been aware that earthquakes equal tsunamis. The tremors of the earthquake were unusual, and this was my first experience with a power outage, so I escaped as soon as the shaking stopped, recognizing that this was abnormal. That’s how I survived and am here today.

I run an acupuncture and massage clinic. On that day, I had just finished treating a patient when the quake hit. Things fell all at once and the power went out, so I was surprised. My house is on the same property, so the first thing I did was to check on my parents, who live in the main house, and they were fine. My older son happened to be off duty at work and was home. Fortunately, I put my parents in my son’s car and told them to flee to a shelter. Since I have low vision, my wife put me in her car, and we fled.

I was aware that living near the ocean meant that after an earthquake, there would be a strong possibility of a tsunami. I had experienced dozens of earthquakes since I was a child, and I had also experienced tsunamis three or four times, though not to the level experienced on March 11, 2010. My father was born in 1926, so he escaped after experiencing the Sanriku Tsunami of 1933 and the Chile Earthquake Tsunami of 1960. We evacuated immediately due to concerns about his advanced age. This was the third tsunami, and I think my father is a lucky man to have survived.

Surprisingly, I kept my cool, took my cell phone, charger, radio, batteries, and digital camera, and carefully locked the front door. I didn’t touch any of my things because I planned to clean them up later when I got home. I am also a board member of an organization, and I took their deposit money with me. There was a blackout that prevented the cash register from opening, so I couldn’t take out the money from my business.

As I listened to the radio that night, it was announced that Rikuzentakata City had been destroyed. But I couldn’t imagine the scope of destruction. During the day, my friends in town would tell me about what they had seen and heard, saying that it was very unusual. At nightfall, the town of Kesennuma turned red, apparently because of a fire. The sky was red. I found out later that Kesennuma was a sea of fire, as you know.

I listened to the radio, and they said there were a lot of corpses, but I couldn’t imagine it. There are seventy-seven households in my neighborhood association. Seven households on higher ground were safe, but seventy households on the plains were all washed away. Two or three people per household means that there were about two hundred residents, and eighteen of them died.

The nights were cold. Women and children stayed in the Japanese-style room, where there were blankets for emergency evacuation and a stove for warmth. The men were in the hall or conference room. We sat near the reflective stove and warmed ourselves, but the floor was concrete, so it was cold. Then, I thought of something and put on a plastic garbage bag, which somehow kept my feet warm. I tried to sleep until morning, but I could not. That’s how I spent the night. That day, I was only able to eat a small rice ball.

I was a member of the board of directors of the general affairs department of the neighborhood association. Three or four years before the earthquake, I was in charge of creating a disaster prevention organization led by the government and updated the levels of stockpiled food and other items at evacuation centers. Unfortunately, some of the items such as instant noodles were only increased marginally. Just one year before the earthquake, there was a Chilean earthquake and tsunami warning. At that time, we evacuated from morning till night. Because of this experience, some people suggested that we should increase our stockpile of food, so we increased it a little. We also received donations of blankets from each household and stocked the shelter as well as purchasing a new oil stove.

Since the Chilean Earthquake Tsunami in 1960, we had evacuation drills every year in May. The entire neighborhood association had been conducting drills, which was a blessing in disguise. So everyone knew where to escape too. I am sorry to say that many people who did not participate in the annual drills perished. If you don’t have an awareness of where to run to in case something happens, you won’t be able to think of it in an emergency. I was able to save my life because of my training. In addition, as an officer of the neighborhood association, I had to take the initiative in participating in drills. I now think that training was and is very important.

Most of the people in the town evacuated to a large community center. From the second night, by a strange coincidence, I was evacuated to a community center in a small mountain village called Hikamisan. I felt that somehow I was being protected in order to survive. As the pillar of a family of six, I was aware that I had to protect them.

I tried to figure out how to survive each day. For starters, I needed food and water. I was so grateful for the support materials that came in right away. There was no shortage of food, so all I needed was clothing and hygiene products.

Our family slept in what was called a dining room-kitchen area, with wooden flooring and a thin carpet. We lined up cushions (zabuton) on the floor and slept with about three blankets on top of each other, but it was still cold. The Self-Defense Forces arrived on the third day, and about a week later, we received bedding (futon) as a relief material. I laid out the futon and slept on it, and it was warm. However, when I folded the futon in the morning, cold air came in from underneath and when combined with my body heat made me damp, but I was really glad that cotton futon was so warm.

More and more support materials arrived, and the room was filling up. The houses on the higher ground were safe, but they were damaged and had no provisions. Since there was nothing in the stores, we had to distribute relief supplies to the local people as well. There were only two families in the community center. The other family was a couple, both school teachers, who were not here during the day because they had to work, and they had two little girls. I had a son who had just graduated from junior high school, elderly parents, and a wife. In the end, I was like the office manager.

The husband of the other family was a teacher at Takata High School and his wife was our second son’s fifth grade homeroom teacher. I felt fortunate to have spent time with this couple, as they were helpful in advising us on my son’s higher education options. Later, we were asked by the prefectural government to take secondary shelter in a hot spring, so we moved to Nishiwaga Town, which is located inland of Iwate Prefecture and borders Akita Prefecture.

At the end of March, we finally got cell phone service. It was difficult to figure out what to do on a daily basis, and to also plan for the future. One day, a business colleague in Morioka asked me to relocate there. My intuition told me, “Well, Morioka is nice, too”. So I decided to move to Morioka with my family of six.

My son had taken and passed the Takata High School entrance exam on March 9, two days before the earthquake. Initially, I had convinced my son to go to Takata high school and he wanted to go but then we decided to look for a high school in Morioka. This would normally be difficult, but we were able to get a special exception applied. We were told that it would be okay as long as all family members relocated together, and in mid-April my son had an interview and entrance ceremony at the high school in Morioka. At that time, my wife and I drove about an hour and a half from Nishiwaga-cho to Morioka to look for a house. After considering a floor plan that would accommodate a treatment center due to my job, we decided on a slightly larger house since we are a family of six and moved in at the end of April. By the end of May, we were ready to open an acupuncture clinic. We looked forward to getting back to our daily lives as soon as possible.

At the time, Mr. Kenichi Chiba was an alderman and an external auditor for our business. He immediately made himself available to support us. He was very helpful and especially worked with me to obtain living necessities from the government for survivors. I am grateful to him for helping us get off to a relatively smooth start in Morioka.

Around July, I was asked to share my experiences as we were starting a volunteer group to support the recovery of the disaster-stricken areas, and I was also asked to help a little with the secretariat of the association. I was not yet settled into my job, and inwardly I thought it would be tough. As a result, I became the Secretary General of the association. While I was concerned about my own work and life, I really wanted to do something to help people. I thought about what I could do. At one time, it was said that as many as 3,000 or 4,000 people were evacuated inland. It was suggested that we create a place where these people could interact with each other. We immediately organized an exchange meeting, the first of which was given by Mayor Futoshi Toba (Rikuzentakata City). It was a great success, with about 60 people, including local citizens, in attendance.

We held about three exchange meetings with the hope of building a community and encouraging each other through these activities. However, many of them preferred to stay home. I would reach out wherever I was needed to support these people.

I lost everything but my life during this disaster. I had no time to be depressed because I had to protect my family. My son had to continue his education, I had to support my aging parents, all while working. I try to live positively and look forward to a better tomorrow. My wife happened to be from Morioka and had several relatives and connections but we didn’t approach them for direct support however, they were great at supporting us spiritually. My clinic was new to the area, so I handed out business cards and did some advertising but it was still a challenge to increase the number of patients. This situation was very stressful to me.

We were highly motivated to start over and live independently. The driving force behind this was volunteering for community activities outside of work. I wanted to actively increase my interaction with new people, and it was Mr. Kenichi Chiba who gave me the opportunity to do so. My volunteer activities did increase my interaction with various people and gave me a variety of memorable experiences. One example is the Singing Cafe. On Sundays, a band would play at the cafe and we invited people from the community who loved to sing. It was energizing to sing out loud.

When we invited a man named Aramaki Tsutomu to give a concert at Morioka Kenmin Kaikan, the stage was filled to capacity and everyone was so moved by his voice that they all cried at the end. I helped with the management of the concert, and felt that the singing was good.

His land has already been purchased by the city.

I saw a documentary film about a group of people who are planting cherry blossom saplings in the areas where the tsunami reached. It is a short film, and we worked on its independent screening. Morioka was the first inland city to host the event, which was also a great success. We appealed to people to be aware of disaster prevention on a daily basis. The person who made the film and the representative of the group that planted the cherry trees spoke, and everyone was very moved. We all felt very emotional after the film and the lectures. I am pleased to say that our activities were a pioneering success, and I am confident that it will lead to more screenings.

Two years ago November, eight members of a volunteer organization and I participated in the planting of saplings in the disaster area. It was humbling to be able to return to my hometown and directly help in this way. I heard that the best time to plant cherry trees is in March or November. When I visited last December, it coincided with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s visit to the disaster-affected areas.

In this way, volunteering has helped me in my work and has given me a sense of purpose in my life. Honestly, in terms of work, our income is not even half of what it was before the earthquake, it is tough. However, my second son graduated from high school and will be a junior in college in April. Since he was little, he wanted to follow in my footsteps and practice acupuncture and moxibustion therapy, but now he is in the nursing department at university because it will support his medical studies. I hope that he will be able to work at a hospital in the future, because self-employment can be quite difficult.

I will do my best in Morioka for another two years, and after that I am undecided. I am often asked, “What are you going to do from now on”? But I am at a loss to reply. I have a desire to return to my hometown, but I am not ready to go back yet. The soil has been filled in, but it will be three years before the bulking is finished. The earliest construction will start this November, but it will take five years before the buildings are completed and the shopping district. After which the townscape will be largely completed. I am sure there will be many more reasons that will affect my decision in the future. It is a complicated situation because I realize that I have no choice but to continue living in Morioka, where I can make a living. The people here want me to stay, and my former patients in Takata town would like me to return. I wish I could do both.

I have always said that I want everyone to remember the disaster. However, I really want to forget about it for a while. I have mixed feelings: I want everyone to remember, and I want to forget a little.

What I wanted to express here today, as I said at the beginning, is that we never know what will happen anywhere. Not only tsunamis, but also volcanoes, floods due to heavy rains, fires, traffic disasters, and so on. We have no idea what the future holds. Decisions made in those moments of tragedy can make the difference between life and death.

Always make sure you have a safe place to evacuate to, or at least a place to meet up with your family. Also make sure to prepare emergency supplies. My experience reminds me that each individual’s attitude and preparedness could surely save them. Whenever I am invited to give a lecture, I talk about how preparation can make the difference between life and death.

Thank you all for listening.

Mr. Kenichi Chiba

(Representative Director, Iwate Prefecture Liaison Council of Intractable Disease and Disease Organizations)

The president of Iwate Nanbyoren (Intractable Disease Association)

Rikuzentakata City was truly a beautiful town. There were thousands of pine trees and a long sandy beach where even beginners could swim. We used to bring our children here year after year to make memories. However, as you can see, everything was taken away.

Rikuzentakata City was truly a beautiful town. There were thousands of pine trees and a long sandy beach where even beginners could swim. We used to bring our children here year after year to make memories. However, as you can see, everything was taken away.

In Rikuzentakata City alone, about 1,800 people died, including those who are considered missing. A friend of mine also lost his life, but I don’t know if he couldn’t or wouldn’t have escaped. He lived with his elderly father. I think that he was probably unable to escape and was carried away by the tsunami waves. I think that those who could not or did not escape thought that the tsunami would not come inland this far. Tsunamis can strike three or four kilometers inland at a speed faster than a bullet train. Unless you have experienced a tsunami, you cannot understand the horror of such an attack.

As Mr. Sato mentioned, since the big tsunami in 1933, the residents must have been quite thoroughly prepared for it, including annual evacuation drills. Still, there were many who did not or could not escape. Many were categorized with disabilities and other ailments. I believe that more than twice as many people in this category died as non-afflicted people.

Mr. Sato and his family of six came to Morioka with nothing. And consequently lost everything. He started his business using the skills he possessed, and is now back on track, but that is not the end of his story. About 1,500 people have evacuated to Morioka, and he provides health counseling for them. He is working to do something for people in similar situations and to provide emotional support to those affected. I asked him to give a lecture because I wanted everyone to know that he is doing this kind of activity even though he is struggling to survive as well, after the disaster.

While there are people like Mr. Sato who are trying their best to survive amidst the ruins, there are also others who have become completely despaired with their lives and are dying alone. This is happening one after another in the temporary housing environment. We appreciate your understanding and will continue to make particularly strong requests to the government and other agencies for increased support. Thank you very much.